Connacht Tribune 7th January, 1933 p.11 (abridged)

Wikimedia Commons

Kilmacduach (Cill Mac Duach – Mac Duach’s Church), County Galway, three and a half miles from Gort, is situated in rather bleak country on the Clare border. St. Colman Mac Duach founded a monastic settlement there in the seventh century. He spent the earlier part of his life as a hermit in the wilds of Clare, and many are the legends told about him and the holy wells dedicated to him in the neighbourhood. Then, having the good fortune, like most of the Connacht saints, to belong to a royal family, he received a grant of land at the present Kilmacduach from his kinsman, King Guaire.

There are several ecclesiastical ruins. The Cathedral of the old diocese of Kilmacduagh is a large building, but ruined. The west gable and doorway and part of the side-wall, built of large polygonal stones, are ancient, and probably part of St. Colman’s original church; but the rest of the church is fifteenth century. There is a good doorway in the north wall of the nave. North of the Cathedral is Teampal Iun (St. John’s Church) with a fifteenth century nave. The east windows, round-headed, displays the graceful Irish Romanesque style at its loveliest. The opes are only eight and a half inches wide but eight feet high, with rich mouldings on the internal jambs and external reveals. A slender torus encloses the whole window. The south windows, of one light, with a hood moulding, is almost as beautiful. The piers of the chancel arch are transepts, but preserve some of the best points of the Irish Romanesque style. They consist of three engaged pillars, with sculptural capitals and bases. There are quoinshafts to the chancel, beautifully pointed. This church was evidently built between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, before the Norman invasion disturbed the place of the bishops of Kilmacduach.

There are remains of several other churches, and some tombs, notably those of the O’Shaughnessys, in whose territory the village stands. St. Colman’s reputed tomb is shown nearby.

The Round Tower is one of the finest in Ireland, and is nearly perfect. It belongs to the”fourth” type, with a typical semicircular arch to the doorway, built with three stones. It was probably built at the same time as Teampul Iun. It is 112 feet high with a base circumference of sixty-five and a half feet. The base has a plinth of large stones dressed to the round and the top has been restored with inferior masonry. The tower leans some four feet out of the vertical, the result probably of a subsidence of the foundations, though cannon balls fired at it by Cromwell’s soldiers is the reputed cause. The numerous windows are triangular, with inclined sides. From the tower there is a wonderful view, as the builders intended there should be, across miles of country, and over a good part of Galway Bay.

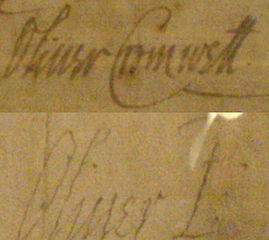

Ed. Lynam